Hyde, J., Le Grice, J., Moore, C., Groot, S., Fia-Ali’I, J., Manuela, S. . (2017). He Kohikohinga Rangahau: A Bibliography of Māori and Psychology Research. School of Psychology, The University of Auckland

This webpage has been set up by the Māori and Pacific Psychology Research Committee to support non-Māori staff and postgraduate researchers who wish to include Māori and Pacific people as part of their research, and do so in a way that treats all those involved respectfully.

http://www.hauhake.auckland.ac.nz/

Le Va. (2009). Let’s Get Real: Real Skills for People Working in Mental Health & Addiction. Real Skills Plus Seitapu: Working with Pacific Peoples. The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development, Auckland.

McFaull-McCaffery, J. (2010). Getting started with Pacific research: Finding resources and information on Pacific research models and methodologies, MAI Review, 2010:1.

Anae, M., Coxon, E., Mara, D., Wendt-Samu, T. and Finau, C. (2001). Pasifika Education Research Guidelines. Ministry of Education, Wellington.

Tiatia J. 2008. Pacific Cultural Competencies: A literature review. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Cheung, M., Gibbons, H., Dragunow, M. and Faull, R. (2007). Tikanga in the Laboratory: Engaging Safe Practice, MAI Review, 1(1).

Cunningham, C. (1999). Māori research and development. Health Care & Informatics Review Online, 3(2).

Furness, J., Nikora, L., Hodgetts & Robertson, N. (2016). Beyond ethics to morality: Choices and relationships in bicultural research settings, in Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 26:75-88.

Hodgetts, D., Chamberlain, K., & Groot, S. (2012). 20 Reflections on the visual in community research and action. Visual methods in psychology, in Reavey, P. (Ed). Visual Methods in Psychology: Using and Interpreting Images in Qualitative Research. London: Routledge.

Hudson, M., Milne, M., Reynolds, P., Russell, K., Smith, B. (2010). Te Ara Tika Guidelines for Māori Research Ethics: A framework for researchers and ethics committee members. Auckland: Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Mc Creanor, T. (2004). Anti-Māori Themes. https://trc.org.nz/theme-1-p%C4%81keh%C4%81-norm

Martin, K. (2006). Please Knock Before You Enter: An Investigation of how Rainforest Aboriginal People Regulate Outsiders and the Implications for Western Research and Researchers. PhD thesis, James Cook University.

Moewaka Barnes, H., Henwood, W., Kerr, S., McManus, V., & McCreanor, T. (2011). Knowledge transfer and indigenous research. In E. M. Banister, B. J. Leadbetter & E. A. Marshall (Eds.), Community-based appraoches to knowledge translation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Moewaka Barnes, H., McCreanor, T. & Huakau, J. (2008). Māori and the New Zealand values survey: The importance of research relationships, in Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences online, 3(2): 135-147.

Pohatu, T. W. (2005). Ata: Growing respectful relationships. Unpublished manscript. Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. Manukau.

Royal Society (2017). Mentoring Guidelines. https://royalsociety.org.nz/what-we-do/research-practice/mentoring-guidelines/he-waka-eke-noa-mentoring-in-the-aotearoa-new-zealand-research-community/

Walter, M., & Andersen, C. (2013). Indigenous statistics: A quantitative research methodology. London: Routledge.

These are useful resources that compile Māori and Pasifika psychology literature, broadly conceptualised, and listed in a thematic structure that validates Māori and Pasifika psychologies. The resources will be useful for staff and students who are interested in relevant topic based knowledge on Māori and Pasifika psychologies.

Hyde, J., Le Grice, J., Moore, C., Groot, S., Fia-Ali’I, J., Manuela, S. . (2017). He Kohikohinga Rangahau: A Bibliography of Māori and Psychology Research. School of Psychology, The University of Auckland

Fia’Ali’i, J. T., Manuela, S., Le Grice, J., Groot, S., & Hyde, J. (2017). ‘O le Toe Ulutaia: A Bibliography of Pasifika and Psychology Research. School of Psychology, The University of Auckland.

http://www.royalsociety.org.nz/programmes/funds/marsden/application/vision-matauranga/

Q. How do I set up a research project, and reflect on research questions, so that it is ethically sound for Māori?

A. See Te Ara Tika Guidelines for Māori Research Ethics for guidance on, and considerations for, setting up a research project.

Q. How do I engage in research in a way that will mutually enhance Māori communities who are participating in the research, as advisors, and/or recruiters or participants?

A. See Te Ara Tika Guidelines for Māori Research Ethics or visit Kaupapa Māori website for guidance on aligning research with community aspirations.

Q. How do I engage with Māori who I have identified as having some expertise or stake in the communities I am interested in consulting with/taking part in/being interviewed for my research project?

A. Visit Kaupapa Māori website for guidance on research relationships and engagement.

Q. What research has been done with Māori in the general topic area that I want to research?

A. See He Kohikohinga Rangahau: A Bibliography of Māori and Psychology Research for listed research within particular topic areas. We are working on producing an update in 2016!

I started my PhD without an explicit awareness of my own knowledge about mātauranga, tikanga and te reo Māori. I was also frequently questioned about whether or not I was actually Māori. I had however, been born in Rawene (Hokianga) to a Māori mother (Robyn) and Pākehā father (Chris), and had some beautiful experiences to make meaning of being Māori with my prolific Sarich, Toia (Ko Ngāti Korokoro, Ngati Wharara, Te Pouka, Te Mahurehure ngā hapu; Ko Ngāpuhi te iwi) and Morgan, Harris (Ko Ngāi Tupoto te hapu; Ko Te Rarawa te iwi) whānau. It was from the central basis point of my Māori identity (my mum, nan, cousins, aunties, uncles, grand aunties and grand uncles) that I took roots in kaupapa Māori research, attending to Māori academic understandings of what it means to be Māori within the grounds of my research topic (Māori and reproduction). I attended hapu wananga, talking to people about my research and sharing ideas, offering to take notes, and getting to know more relations than my immediate whānau. This laid down the whariki to move confidently in Māori spaces. This meant I was able to communicate who I was in the context of my relations, when networking with people outside of the hapu spaces of marae, and whānau homesteads.

Broadening connections from my whānau to my hapu (and to an extent, my iwi) assisted me with a connection to a raft of skillsets and expertise. Interviewing people within my hapu was better than I could have imagined. The mātauranga they shared was familiar. It was connected to shared histories of our whenua. It was simultaneously invigorating and novel, but contained patterns of familiarity that allowed me to make meaning and connect. It allowed me to reflexively identify how their descriptions of knowledge and practice applied to my identity as Māori and how this in turn, related to mātauranga and tikanga Māori – the repertoires and patterns of my life.

As a PhD student, learning how to do research ethically, maintaining assurance of confidentiality and anonymity of accounts, was paramount. Researching among people who may know one another, and could be potentially identified meant there was no room for error. Information I was privy to in setting up interviews, and that was shared in the interviews, did not go any further than me. Quoted material was often selected on the basis of not being identifiable, and key identifiable information was changed. The knowledge produced through this research has a strong core with mātauranga Hokianga, but also extends more broadly through the country with interviews conducted in areas further afield, and including participants with diverse hapu and iwi connections, offering a solid contribution as mātauranga Māori. This is important to validate in the discipline of psychology where our ways of life, patterns of practice, and social meanings are invisibilised, denied, or appropriated to reduce the meaning this has in our lived experiences.

Given the importance of validating local knowledge bearers within the community, as a more experienced researcher, I now give participants the option of being named in relation to their material or for their contribution to be anonymous, at the outset. This involves a more time consuming process of going through summary reports of participant interviews to identify which areas to be named or remain anonymous. However, as a researcher who has been supported by their hapu to develop a research profile, through the quality of the knowledges shared by the hapu, and developing analyses that attend to key questions in psychology, this is vital. It is important to validate the hapu individuals who collectively hold the answers to psychological challenges faced by our people, and the capacity to enact community solutions.

My background

I am a non-Māori researcher whose background is in linguistics. The type of research I do covers various aspects of language. I am interested in how speech and language develops in children, how to adapt English language assessments into other languages and multilingualism in the communities of New Zealand. Given my interests it‘s not surprising that I have ended up doing some of my research with the Māori and Pacific Island communities.

Looking back to when I first became involved in research with both communities I feel somewhat embarrassed. I know that I made mistakes culturally because I made assumptions about how to go about doing the research. When we have been doing a particular type of research a while we really don’t stop to consider whether or not it’s appropriate to always do it that way. I don’t consider myself an expert but over time I have learned the following:

Lesson 1: Be humble and respectful

I know more about language and linguistic research than the average person because of my training. However, I am now mindful that the way I generally do linguistic research is based on a tradition established with numerous studies into English and other European languages. A powerful example of why I should question this was brought home to me while working on a child language project in Samoa. I was invited to come along to a therapy session with a child with Downs Syndrome. This child had an older sibling aged around three who was also present. While observing the session I became increasingly aware of how still and focussed the three year old was during the entire time. This struck me as unusual given the interactive, very verbal, caregiver supported studies that I was familiar with from numerous child language studies. I realised that what is typical for Western children is not necessarily the norm for children from other cultural backgrounds. If I am going to do meaningful relevant research, I need to step back and cede the power to those who have more experience than me regardless of academic qualification.

Lesson 2: Take the time to build a relationship with the community

With the first lesson in mind, I found it important to spend time listening to, observing, and learning from the community and my students. Maybe the research does not happen quickly but having a relationship builds trust. That’s critical to the success of the project because every step of the research is a collaboration between researcher and community. Having a relationship with a community would, of course, seem to contravene the guidelines of ethical research. However research with Māori and Pacific participants is not going to happen if this doesn’t already exist.

A good example of relationship building is a project that I currently have underway. I have a Māori speaking student who is working as a RA for me on a Māori adaptation of an English language parental report. Progress on the project has not been quick but it has been enlightening. We have spent countless hours discussing the motivation for creating the adaptation and how to adapt a tool that is entrenched in a specific world view. Spending so much time laying the groundwork may seem a total waste. However, the outcome will be meaningful collaborative research where he and I are learning from each other.

These are some of the networks relevant to Māori research within a psychological scope, though this list is not exhaustive or all encompassing. There are many more relevant organisations, agencies and initiatives that are not listed here. Key contacts can be found on the related webpages, or are listed where relevant.

National standing Committee on Bicultural Issues is a branch of The New Zealand Psychological Society http://www.psychology.org.nz/about-nzpss/nscbi/#.Vmf3W7h97IU

Pasifikology is a network of Pasifika psychologists, graduates and students of psychology http://www.pasifikology.co.nz/

Le Va is a non-government organisation that provides resources and support for Pasifika people in the areas of mental health, addiction, public health, suicide prevention and education http://www.leva.co.nz/

Nga Pae o te Maramatanga is New Zealand's Māori Centre of Research Excellence (CoRE), hosted here at The University of Auckland, through Te Wānanga o Waipapa http://www.maramatanga.co.nz/

Te Kupenga o MAI, the Māori and indigenous programme, is a New Zealand-wide support network for Māori and indigenous post-graduate students http://www.mai.ac.nz/

Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui is a national centre of evidence based workforce development for the mental health, addiction and disability sectors in New Zealand http://www.tepou.co.nz/initiatives

Te Puni Kokiri is the government's principal adviser on the Crown's relationship with iwi, hapu and Māori, and on key Government policies as they affect Māori https://www.tpk.govt.nz/

Waka Hourua is the partnership between national Māori health workforce development organisation Te Rau Matatini and national Pacific non-government organisation, Le Va. Te Rau Matatini and Le Va have come together to deliver Waka Hourua, a suicide prevention programme for Māori and Pasifika communities http://wakahourua.co.nz/programme

Te Rau Matatini provides a strategic focus for Māori workforce training, education and capability building solutions for the advancement of indigenous health and wellbeing http://matatini.co.nz/

Te Ropu Wahine Maori Toko i te Ora (Maori Women’s Welfare League Inc), is a prominent, reputable Maori organisation in New Zealand’s social and commercial environment http://mwwl.org.nz/

National Māori takatāpui initiatives - see the following link to a fantastic free resource for takatāpui, their whānau & communities that provides information about identity, wellbeing and suicide prevention produced in partnership with Tiwhanawhana Trust: http://shop.mentalhealth.org.nz/product/758-takatapui-part-of-the-whanau and an amazing doco series http://www.nzonscreen.com/title/takatapui-2004 that explores how the term takatāpui was undermined through colonisation and includes interviews with takatāpui (specifically renowned queer activist and art historian Ngahuia Te Awekotuku)

Treaty Resource Centre – He Puna Mātauranga o Te Tiriti provide 'Making Sense of the Treaty' courses for organisations to host. Hosts provide the venue and a cup of tea for participants. There is no charge for facilitation or resources. https://trc.org.nz/making-sense-treaty-course

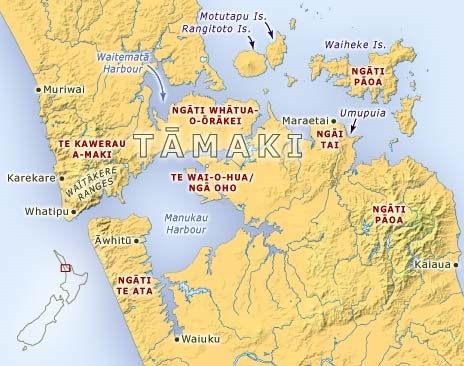

Tangata whenua of Tāmaki

Image sourced from: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/map/1039/the-six-auckland-tribes

Several iwi and hapū inhabit the Tāmaki (Auckland) landscape. These include Ngāti Pāoa http://www.ngatipaoaiwi.co.nz/, Ngāti Whātua-o-Ōrākei (a hapū of Ngāti Whātua iwi) http://www.ngatiwhatuaorakei.com/, Te Kawerau A-Maki http://www.tekawerau.iwi.nz/, Ngāi Tai http://www.ngaitai-ki-tamaki.co.nz/aboutus.html, Te Wai-o-Hua/Ngā Oho (hapū of Te Ᾱkitai) http://www.teakitai.com/index.php and Ngāti te Ata (a hapū of Tainui iwi) http://www.waikatotainui.com/. In some research topics it may be appropriate to collaborate and develop a relationship with tangata whenua.

University of Auckland centres and initiatives

I, Too, Am Auckland is the culmination of a Nga Pae o te Maramatanga summer internship that engages with Māori and Pacific students’ everyday experiences of racism here at The University of Auckland, and considers possible solutions. http://mediacentre.maramatanga.ac.nz/content/i-too-am-auckland

The Equity office provides scholarships, advice and support for Māori and Pacific students to assist with success at the University https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/eo-equity-office/eo-information-for-students.html

James Henare Research Centre, based at the University of Auckland, is a research centre focussed on community research within the Tai Tokerau (Northland) region https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/Māori-at-the-university/james-henare-Māori-research-centre.html

Te Wananga o Waipapa is the School of Māori and Pacific Studies within the Faculty of Arts http://www.arts.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/schools-in-the-faculty-of-arts/te-wananga-o-waipapa.html see also the related webpage about our marae here at The University of Auckland, Waipapa marae http://www.arts.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/schools-in-the-faculty-of-arts/te-wananga-o-waipapa/Māori-studies/waipapa-marae.html

School of Psychology initiatives

The Māori and Pacific Psychology Committee supports Māori and Pacific initiatives within the School of Psychology and is comprised of Māori and Pacific staff and allies within the School of Psychology. See our 2015 annual report (below), and newly refined mission statement. Contact co-chairs Hineatua Parkinson atua.parkinson@auckland.ac.nz or Sarah Kapeli s.kapeli@auckland.ac.nz for any related queries.

The Tuākana programme provides initiatives for social and academic support for Māori and Pacific undergraduate and postgraduate students through their tertiary study: http://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/for/Māori-and-pacific-students.html

Māori and Pacific Psychology Research Group provides a support structure for Māori and Pacific postgraduate research students through their tertiary study http://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/our-research/research-groups/Māori-and-pacific-research-group.html

School of Psychology ethics advisors are also available to assist with ethics related queries.

Herangi-Panapa, T. P. M. (1998). Ko Te Wahine He Whare Tangata, He Waka Tangata: A Study of Māori Women's Experiences of Violence as Depicted Through the Definition of Whakarite. (Master of Arts), The University of Auckland, Auckland.

Jungersen, K. (2002). Cultural safety: Kawa Whakaruruhau – An occupational therapy perspective. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(1), 4-9.

Pihama, L. (2001). Tihei mauri ora: honouring our voices: mana wahine as a kaupapa Māori theoretical framework. (Phd), The University of Auckland, Auckland.

Smith, L. (2006). Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous People. London: Zed.

Smith, T. (2009). Aitanga: Māori Precolonial Conceptual Frameworks and Fertility: A Literature Review.

Tate, H. A. (2010). Towards Some Foundations of a Systematic Māori Theology: He tirohanga anganui ki etahi kaupapa hohonu mo te whakapono Māori. (Doctor of Philosophy), Melbourne College of Divinity, Melbourne.